(A Small Postal Tiff Between Colombia and Great Britain in 1867)

The following article appeared in the 4 April 1867 edition of The Times of London:

“The British Consul at Carthagena (sic) having complained to the Commodore on the station that the letter bags of British residents were opened and detained by the Authorities there, Her Majesty’s ship Doris was dispatched from Port Royal on the 23d (sic) February to inquire into the circumstances, and to demand that the practice be discontinued. The Doris arrived at Carthagena on the 26th and Captain Vesey immediately communicated to the Governor the object of the mission, which was to secure to the British Consul the same advantages in postal matters as were conceded to the French and American consuls at that port. The Governor at first stated that he had not the power to grant the request. The Doris, therefore, sent an armed force on board the Colombian (sic) steamer of war Colombian, and she was seized and held possession of. The Governor was stubborn until these measures were resorted to. After two days’ consideration the Governor found that he had the power to grant the request, and the British Consul assured the captain the difficulty was arranged, and that the British interests would not be interfered with for the future. Affairs having been settled, the of cers of the ship were invited ashore and kindly entertained by the inhabitants. The Colombian was released on the 1st March. The Doris left Carthagena on the 3d (sic), stopped at Santa Martha on the way back to Jamaica, and arrived at Port Royal on Wednesday evening, the 6th last.

The following additional particulars in reference to the Carthagena affair have been sent to us by an eye witness:-

The natives alleged that a private misunderstanding existed between the President and the British Consul. These petty indignities or discourtesy had grown so serious that they had become quite a national question between the President and the Consul. The objection of the British Consul was that a difference was shown to him that was not observed towards the other Consuls. First, his bags were opened. Secondly, unfair tonnage dues were extracted from British vessels, and these dues were not demanded of other foreign vessels. Thirdly, proper respect was not shown to British residents. Representations of these grievances were made by the Consul to the President, without any favourable results. The Consul, therefore, felt it his duty to communicate with Commodore Sir Leopold M’Clintock on the subject, who immediately dispatched Her Majesty’s steamer Doris, Captain Vesey, to Carthagena.

On her arrival dispatches were forwarded to the British Consul to be delivered to the President, and there being considerable delay in obtaining any answer – the authorities showing great indifference and disinclination – Captain Vesey considered it necessary to make some demonstration of earnestness in his demands. Just about this time a steamer belonging to the Government, the Colombian, came into port. The Captain and crew were all Englishmen, but the purser was a native Spaniard (sic!). This vessel is one of only two belonging to the Government. As she arrived, Captain Vesey ordered three boats to be lowered and manned by Marines and bluejackets fully armed. They approached the Colombian, to the great astonishment of the crew. The Spanish purser ordered the sentries to re and prohibit any attempt to board her, but the captain ordered that no resistance should be offered, which created some altercation between the purser and the captain, the latter (more probably the former!) declaring that he would rather die than see an insult offered to his ag. The vessel and the crew were disarmed, and British sentries placed on board, but the Colombian ag was not displaced. Captain Vesey having accomplished the seizure, sent notification at 6 p.m. to the British Consul, that six hours would be granted for the adjustment of the difficulties with the British Consul or he would resort to other measures. The seizure of the Colombian produced intense excitement on shore against the British; the Consul’s life was threatened, and hundreds of the inhabitants paraded the streets with macheats (?machetes, long, sharp knives used to cut sugar cane, a local staple at the time) spikes and other arms, at the same time vowing vengeance and using violent language towards the British officers who had gone ashore. The other Consuls went on board the Doris to request that their property should be respected, and the captain extended the time to 10 a.m. the next day, when he would decide upon the measures to be taken. In the meantime, three hundred men were under arms in preparation to land. Just half an hour before the expiry of the time, a boat was seen coming from the shore, with dispatches from the Consul, to say that an apology had been amply given, and all that had been demanded had been conceded by the President. This put a stop to hostilities, and the Colombian was restored to her captain. The Doris remained in port for a couple of days, and left for Santa Martha.”

In fact, The Times picked up this story from the British Caribbean fleet’s local rag, published in Kingston, the Jamaican Gleaner. The Times must have had further access to information direct from a member of the Doris crew.

The first inkling of the spat comes in the Jamaican Gleaner of 13 March 1967:-

THE DIFFICULTY AT CARTHAGENA

The question which arose, so far back as the end of November last, between the British Consul (who is also packet agent) at Carthagena, and the local authorities, respecting the pretensions of the latter to break open and distribute British Mail, has now come to a crisis, and is involved with others no less serious.

Consul de Fonblanque acting, as it is said, under instructions from H.M.’s Minister at Bogota, had resolutely resisted these unfriendly proceedings, but in vain. Two mails – the one by the Liverpool Steamer “West Indian”, from Colon, and the other by the R.M.C. Packet “Tamar” were violated by the local authorities; but the facts having been reported to Commodore McClintock, H.M. steamer “Doris” was dispatched to Carthagena. As we before observed, the affair has reached its crisis.

The worst feature, perhaps, in this case is, that a provisional arrangement or compromise entered into by Consul de Fonblanque with the President of the States was broken by that of cial whilst the Consul was spending Sunday in the country. –This was the case of the “West Indian” which arrived unexpectedly.

If the accounts which were current in Carthagena respecting the correspondence between the Consul and the local authorities be correct, the latter have placed themselves on the horns of a dilemma, from which, in spite of some questionable quibbling, the Consul has held them firmly.

The same laws which govern the case of in-coming mails, relate to outward; and the authorities, foreseeing some dif culty in getting their correspondence off to Europe, relaxed for their own convenience in the one instance, the decrees which they rigidly enforced against British honour and interests. In the other they acknowledged Mr. de Fonblanque as duly authorized to make up and send mail, but required him as Packet Agent, to receive one. They have therefore done for themselves pretty much what worthy Dogsbody wished he had somebody to do to him.

The postal communication (?Convention) between Great Britain and Columbia was put an end to in the year 1863, but from that time up to November last, its provisions have been continued, by mutual consent, to the great advantage of Colombia, as the postal service costs many thousands a year beyond the sums received as postage. The Steamers of the Royal Mail Company continued to be free of tonnage dues and Custom’s regulations; and all went well till President Mosquera made a decree in August last, by which their privileges were withdrawn, their registers extracted, and the mails subjected to local control. This decree, we understand, has never been noti ed to H.M.’s Government. Hence the present questions.

On the arrival of the Doris, Consul de Fonblanque by direction of Capt Vesey required a postponement of the obnoxious laws until the questions respecting them, then pending between the two Governments should be settled; and also certain explanations of past proceedings which were deemed derogatory to British honour.

To this the President made the usual reply non possamos, Captain Vesey then detained the so called man-of-war Columbia, and noti ed that when he received a satisfactory answer to his requisitions by 10 O’clock p.m. (afterwards prolonged till 10 a.m. next day) he should take further steps.

During the evening and night of the 28th, the greatest excitement prevailed in Carthagena, and pressure was put upon the President to take advantage of the excuse for yielding, carefully provided for him by the British Consul, namely, that Presidents of other States of Colombia had acted differently, and the majority was against him. In due course a satisfactory reply was returned on all the points, the Colombia was giving (sic) and the city relieved of its fears, “We are not afraid of the British Forces”, they said, “these will be under discipline, but who will save us from the rabble that will take advantage of the confusion to plunder us?”

The lesson thus given has long been required, and President Carazo may yet live to thank Doctor Vesey for the bitter but wholesome pill which that able physician has administered”.

The “Gleaner” takes up the story once again on 25 April:

OUR COLOMBIAN DISPUTE

The latest accounts from Bogota bring us the intelligence that the differences between the President and the Congress have been arranged in a satisfactory manner. General Mosquera had to acknowledge that many of his acts lately have been subversive to the Constitution and the laws of the Republic; even the minority who supported the Government in Congress, had to join the majority, having to put a stop to the arbitrary measures of the Ejecutivo. The threatened revolution has thus been averted. The doings of H.M. Ship “Doris” at Carthagena, had reached Bogota, and, as expected generated a great sensation. General Mosquera did not approve of the conduct of the authorities of that place, and retired the exequatur of Mr. Fonblanque, Her Majesty’s Consul. It was at first reported that this gentleman was going to leave; but he has since changed his mind, preferring to await the decision of the British Government. We should not, therefore, be surprised if new complications arise out of the Mail Bag question”.

In the same edition the “Gleaner” prints a report dated 5 April from a Special Correspondent in Carthagena:

“The curtain now rises upon the third scene of this melo-drama “A storm in a mail bag or tonnage doos”, which is being enacted in this city. One of the chief attractions of this class of entertainments is the rapid alterations of fortune suffered by the various characters and by which the spectator’s interest is kept continually at work. The drama now under consideration is full of “startling effects”. At the end of the first scene we nd the poor British Consul weeping over the outraged seal of a mail bag. In the second H.M.S. “Doris” appears, and Captain Vesey – admirably played (by himself) puts an end to the insult heaped on his country, and exits in a blaze of triumph. At this juncture every old play-goer knows that things must take a turn, or how is the second act to be fitted out?

It is difficult to be serious with Colombians, but we must try, after giving a few examples of the difficulty of our task.

It was at one time seriously intended to resist Captain Vesey by force of arms. A patriotic Carthagenian presented the Government with fifty rifles (!) (valued at nine francs each) to assist in sinking the “Doris”, and $800 worth of small shot was bought to be cast into bullets for the destruction of the doomed vessel.

An adventurous carpenter volunteered to go off at night in a canoe, and scuttle Her Majesty’s Ship with his augur.

In a debate on the Mexican question at the Capitol, a Senator opposed sending aid to the Republican party on the ground that they should strike at the root of the evil, and that in the event of the Emperor of the French not withdrawing his support for his “brother” Maximilian, the Colombian navy (one ship of 700 tons) should be sent to Cherbourg to bring Napoleon III to reason – a la Vesey!

President Mosquera is busily engaged correcting the errors of Humboldt, and allows himself to be publicly told that next to Julius Caesar and Mr Pitt he is the greatest man who ever was – or, perhaps, ever will be. So he has “disapproved” his agent here – President Curago – for not having sunk the “Doris” (with rifles and partridge shot aforesaid), withdrawn the British Consul’s Exequatur, and declared null and void the arrangement made by Capt. Vesey. The compromise entered into between Consul de Fonblanque and President Curago (the breaking of which by the letter was partly the cause of the mission of the “Doris”) is to be revived. It is thus admitted that President Mosquera’s decree as to British mail, which has caused all these difficulties, is impracticable.

President Curago – the Agent in Carthagena of the National Government – has been disapproved for breaking the seals of the British Mail; and long before the “Doris” arrived, was ordered to continue his compromise with Consul de Fonblanque. He continued to break the seals and disregarded these orders; and is therefore wholly to blame for all that has happened. – We learn that the proceedings of Consul de Fonblanque up to the arrival of the “Doris” in Carthagena have been approved by Government. We hope shortly to be able to report the same of Captain Vesey’s operations and to give the nale to the second Act. We are no advocates for the use of force, but when a people steeped in worse than Chinese egotism and arrogance, insult British officers, and injure British commerce, what other argument is left?”

The Stamp-Collector’s Magazine soon took up the story and the edition of 1 May reproduced part of the Times story. Strangely, they inserted the following additional phrase – “he (Captain Vesey) at the same time requested the foreign consuls to hoist their flags over their respective consulates at day-break the next morning.” This may have been standard practice in such cases to avoid damaging friendly property, but it is certainly not in the cited articles. But the magazine in its final paragraph did get its priorities right:-

“From a philatelic point of view, a rupture with New Granada (at this time The United States of Colombia) would be very undesirable. Stamp-collectors must always be anxious for the preservation of peace, as war with a stamp-emitting country would result in the partial stoppage of their supplies of stamps, and should a new series be issued, they could only be obtained at an increased cost from the stamp dealers of a neutral country, unless perchance our troops should happen to seize the enemy’s post of ces, and con scate the stock of adhesives”. So much for the loss of life! Philately is now just another excuse to declare war!

The Log Book of HMS Doris is available at the Caird Library at the National Maritime Museum, reference SIS/3. Her home base was Devonport. The Log reproduces a typically military and succinct account of the action:-

26 February 1867

Came to off Carthagena

27

9.25 Consul came on board. 10.45 left the ship saluted seven guns. A demand for an apology was sent to the President.

28

An apology being refused we took possession of the War Steamer “Colombian” and threatened further proceedings.

1 March

Small arm men and boats crew were paraded ready for landing at 10.30. 10.20 Consul came on board with full apology from President.

3

Weighed and proceeded under steam to Santa Martha.

View of Santa Marta harbour, in watercolour by Edward Mark, British Consul there in the 1840s

Life must have been pretty boring aboard a sailing vessel those days – so many days to travel a relatively short distance. Steam improved matters somewhat, but entertainment was still required and often self- devised. Two thirds of the log book are taken up with the efforts of the ship’s artist. There are pen and ink drawings and watercolours of rocks and headlands off Santa Marta. Unfortunately he places Santa Marta in Venezuela! It is to be hoped that the ship’s artist was not also the navigator!

On a more serious note, between 25 and 29 March at Port Royal, Kingston, Jamaica the ship suffers more than thirty cases of Yellow Fever. They had to bury on shore seamen William Spurrel, Henry Jones, and Henry Lucky. Could this have been a case of Mosquera’s Revenge? Probably not. According to the Encyclopaedia Britannica the incubation period for Yellow Fever is from three to six days. The crew were bitten by Jamaican mosquitoes.

But how accurate are these reports and why was the greatest Power on Earth threatening a backward country which had made little or no economic, social or political advances since independence from Spain in 1819 and had no hope of defending itself? The “President” referred to was the President of the State of Bolívar, a constituent of the recently formed Unites States of Colombia, and his correct name was Sr. Gonzalez Carazo. The Colombian “man-of-war” was the Colombia, under the Englishman, Mr. Dinsdale.

In fact the whole episode has little to do with Cartagena at all, but rather with Panamá, another part of los Estados Unidos de Colombia. It had to do with the Postal Convention between the two countries of 1847 and the contract between Nueva Granada as Colombia was then known, and the Panama Railroad Company – of American capital – signed in 1850. It had to do with commerce, with personalities and, of course, money.

The Gleaner was not far off the mark when it likened the episode to a stage play. It transpires that it was more of a Whitehall farce, or, better still, a Gilbert & Sullivan operetta. Communication and distance contrived to ensure decisions were usually overcome by events. Four months could easily elapse between the dispatch of a letter from Bogotá to London and the receipt of a reply. The complication of carrying a letter in those days from Cartagena on the Coast, to Bogotá, is mindboggling, and could well be the subject of a separate article.

THE 1847 POSTAL CONVENTION BETWEEN THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND AND THE REPUBLIC OF NEW GRANADA

This Convention was drafted principally to recognise an unofficial service being offered from quite early on after Colombia’s declaration of independence from Spain in 1819, both on the Caribbean coast and across Panamá, then and until 1903, forming part of the new Republic. It followed upon a similar convention with the French in 1845 but, as this one hardly came into activity until the middle of the 1860s, Nueva Granada depended entirely upon the British Post Office for the carriage of the foreign mails, both inward and outward. The Royal Navy and private British vessels contracted to the Post Office were allowed access to the ports of Santa Marta, Cartagena and Chágres, a small port on the Northeast coast of Panamá destined for oblivion once the Panamá Railroad began operations, and the City of Panamá itself. The first two towns were invariably spelled Santa Martha and Carthagena by the British throughout the nineteenth century. These ports of call were variously interchanged or substituted as the century progressed with developments in trade and changes in communication via the River Magdalena with the interior, especially with the Capital, Bogotá, as indeed were the Consulates/post offices attached to them, until 1881 when Colombia joined the Universal Postal Union and the of ces were closed (with the partial exception of Panamá and Colón). Access was to be free of tonnage dues along with several other advantages to facilitate the assistance being afforded by the British, as well as allowing the carriage of passengers. Remarkably, there was an exception to the prohibition of carriage of freight (imports and exports), and that was to carry on the very Spanish practice of transporting gold and silver bullion and coins!

By now steamships, and in particular those of the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company, were operating in the Caribbean, so that access to coal was essential. Article 7 of the Convention permitted coaling stations to be set up at these ports.

It is ironic that Santa Marta should today be so close to one of the world’s argest open cast coalfields and to serve as the exit point for coal exports overseas. The coal mine, El Cerrejón, as a major Colombian mineral asset was commemorated on a Colombian postage stamp in 1986. Santa Marta was the only city apart from Panamá, visited on the Colombian coast by Anthony Trollope. He was not impressed; he found it dirty, undeveloped and invaded by sand blown up from the seashore. Strange that he makes no mention in his Spanish Main of the imposing cathedral in the city. Backward or not, the Bishop of Santa Marta had always been very in influential politically. These regional differences were to be a bane on Colombian progress throughout the nineteenth century. Nor did the famous Post Office employee / novelist describe the remarkable backdrop to Santa Marta, the impressive Sierra Nevada, capped in snow the year round despite its proximity to the Equator. The weather must have been very poor for him to have missed the sight approaching from the sea.

Note Art. 8: “In the case of war between the two nations (which God forbid),………..this service shall continue……” The importance of the post!

And so to the treatment of the crossing of the Isthmus. Earlier, the New Granadian carriage of the British mails from Chágres to Panamá City had become so irregular that an agreement had been negotiated whereby the job would be undertaken by messengers employed directly by the British. The upkeep of the trail to Panamá from the point where the mails were of oaded from the River Chagrés was to be the responsibility of the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company. The use of private messengers was now specifically recognized under Art. 11 of the Convention.

Tariffs were the object of Articles 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19. Newspapers were to be carried free of charge, a considerable benefit to the locals. Letters to and from Europe were to be charged at one shilling per half ounce. Art. 20 encompassed Nueva Granada’s right to charge two reales (twenty cents of a Granadian peso – about ten pence) for each Granadian ounce weight of letters crossing from Panamá to Chágres and vice versa. In other words, of the postage of a simple letter from Panamá to London of one shilling, five pence would go to the local Government.

The document was signed on 24 May 1847 by Manuel M. Mallarino, the Foreign Minister on behalf of New Granada, and by Her Majesty’s Chargé d’Affaires and Consul General in Bogotá, Daniel Florence O’Leary. The Irishman, O’Leary, had commanded the British Legion which had fought alongside Simón Bolívar during the struggle for independence, and had become a personal friend of the region’s greatest hero.

The Convention, which was to run for five years and was renewable for five years successively thereafter, was ratified during the following year by the then President of New Granada, General Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera.

Mosquera’s Signature

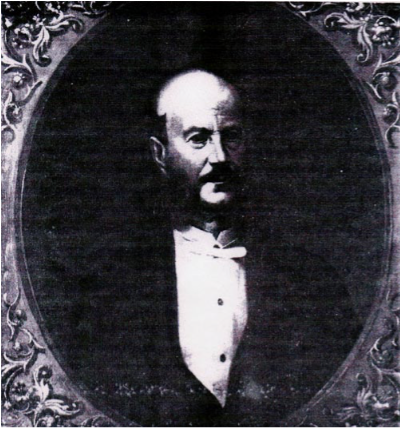

EL GRAN GENERAL TOMAS CIRIANO DE MOSQUERA

Mosquera was a scion of a powerful Popayán family which dominated local politics after the death of Santander until the 1870s. He had been Bolívar’s aide-de-camp. Four times he was elected President, as he delighted in telling his “friend”, Queen Victoria, in 1866 when he was the United States of Colombia’s Ambassador to Europe, based in London. When he was not President, his brother, his son-in-law and assorted other relatives and Popayán politicians were. Another brother was Archbishop of Bogotá.

He ruled the country from 1845 to 1849 as a Conservative, re-emerging in 1861 as a Liberal, “Liberal” in those days meaning conservative but anti-clerical.

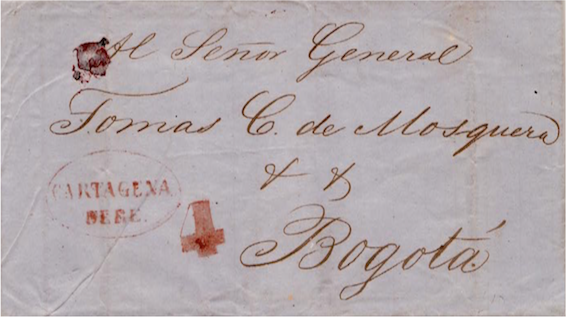

Letter sheet addressed from Cartagena to General Tomás C. de Mosquera in Bogotá

As well as being famously bad-tempered, he was particularly vain, inventing grand titles and decorations, and designing uniforms in which he had himself portrayed in oils. His outlandish moustache and whiskers did, however, have a purpose. In a battle on one occasion a bullet hit and disfigured his jaw. The resultant defect in his speech left him open to ridicule on the part of his opponents.

He was cunning and calculating. At the end of his rst term he decreed the liberation of the export of gold and silver, promptly setting up shop in Panamá as the most prominent dealer in precious metals! Earlier in his career he had settled in business in New York for a few years and left declaring bankruptcy. Just before ending a second term he legalized the import and private ownership of rearms. The purchase followed of 10.000 rifles from England and after arming his followers in the Cauca region he marched on Bogotá and assumed power once again!

As a general he was astute and successful. As President he dreamed of modernizing Colombia, recognizing the importance of steam power, particularly for transport by ship and by rail, communication being the greatest challenge confronting the country. He studied science, setting up the first real library of importance in the northern half of South America (hence The Gleaner’s reference to Humboldt) and he was a member of several European Science Institutes. However, his terms in office were marked by regional differences which caused continual conflict, confrontation with the Catholic Church (he could well be known as the Colombian Henry VIII for his confiscation of Church property) and, above all, the total lack of funds for development. Practically everything he did ended in failure, although his reform of the postal service was a partial success despite British criticism. Given the difficulties of terraine, weather and politics it was a miracle that the system worked at all. After all, gold was regularly transported through the post in the absence of paper money, and it arrived. It wouldn’t today.

The Times of 29 January 1867 reports on one of his ts of temper, leading him to offer his resignation:

“The New York papers today furnish details regarding the resignation of General Mosquera, the President of New Granada (or, as the country has lately been designated, the United States of Colombia). The resignation was tendered on 6th December to the Supreme Court but that body refused to accept it or to hear him in relation to it. The reasons assigned by the General are stated to be that the Treasury is empty and cannot be replenished, that the Church is in open opposition to him, that the Governors of the States refuse to obey his orders, that a spirit of anarchy prevails throughout the Union, and, finally, that the people of Colombia are not worthy of him as a ruler”.

The Panama Mercantile Chronicle writing apparently in the interests of the clerical opposition, observes:

“What right has Mosquera to complain? He and he alone has lighted the torch of revolution and then, to shield himself from the responsibility of what he sees coming up, endeavours to forego it by tendering his resignation. The Supreme Court is right not to accept it but rather to force him to bear the responsibility of that of which he is the sole cause. General Mosquera, not content with the Government of the State, sought to interfere also with the Government of the Church, in direct violation of the Law passed during the administration of General Lopez, in the year 1853, which declared the Church independent of the State and tried to force an oath upon the Bishops, contrary to the Canons and the Law of the Land, and then, because they would not swear it, decreed their banishment, and finally put up their antagonism, which his own act had aroused, as a reason for his resignation”.

His last term laboured on for a few more months until he was finally overthrown.

Abroad, matters turned on his relationships with the United States of America, to a lesser extent with France, and above all, with Great Britain and Ireland. After all, Britain had the technology he pined for and the money. Over the years his feelings for the British ranged between respect and hatred. It was he who had negotiated the original 1847 Postal Convention and he personally signed its ratification. He maintained a lifelong friendship and correspondence from his early twenties with William Wills, a British resident of Bogotá who had married General Santander’s sister-in-law.

Numerous contracts were signed with contractors from England and Scotland for the building of roads and railways as well as the operation of paddlesteamers on the river Magdalena, although few of them ever came to fruition. He used a British architect to design his Library in Bogotá and his portrait was painted by a British artist. Whilst serving in London in 1865 (his title was “El Gran General Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera, Ministro Plenipotenciario de los Estados Unidos de Colombia ante la Gran Bretaña, Holanda, Prusia e Italia” – he also claimed to be related to the Empress Eugenie of all the French through her Spanish family and in this he was probably being truthful; at least it got him invited to dinner at Versailles which no doubt improved his self-esteem no end!), he used his influence to arrange for he and his wife and daughter to make private visits to Greenwich and to Woolwich Arsenal. Both of these closely guarded military establishments appealed to him as a serving soldier. But there were many ill-tempered moments although always couched in the most decorous Victorian diplomatic language, and never more so than in his relationship with the British Post Office.

During his tour of duty in London, on 6 June 1865, he wrote to Earl Russell complaining that a letter addressed to the Embassy had been opened in the post before delivery and demanding an explanation. He went on to suggest a new Postal Convention. After investigation, on 20 July, the Earl replied stating that the letter had been refused upon delivery and returned to the Post Office. Here it had been opened as per normal practice to ascertain the sender, but without breaking the seals on the enclosed packets. The parcel was about to be returned to Panamá when a request came from Mosquera for it to be delivered normally. This was done along with the usual note and the seal of the Returned Letter Office. Did Mosquera contrive to return the package to create a situation where he could address himself directly to Earl Russell on a matter of particular importance to himself and which he had been unable to advance through the normal channels? In his reply Earl Russell maintained that the Postmaster General had no intention of entertaining a new Postal Convention, so the ruse failed.

Later that year, on 20 December, el Gran General wrote to Lord Clarendon requesting a review of postal charges to and from Colombia for what he considered to be excessively high rates. So much so that his operation in London began to use the French postal service which offered direct access to Santa Marta through St. Nazaire, much quicker and less expensive. Unfortunately for him the French only continued the service for a few months.

To rub salt into the wounds, the British managed even to turn Mosquera’s one and only diplomatic success in London, the signing of a Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation, into another bone of contention. Colombia’s copy was sent to that country by the British Post Office which attempted to collect a charge of £18.18.0d! Upon appeal the problem was solved by treating it as a book packet and charging 12/-.

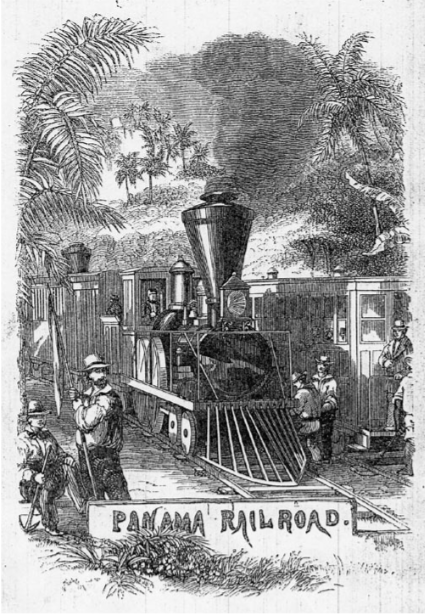

THE PANAMA RAILROAD CONTRACT

Mosquera’s postal difficulties date from the signing of a contract with the French to build a railway across the Isthmus negotiated during his first Presidential term, and signed in Bogotá on 10 May 1847. The Compañía del Ferrocarril de Panamá was sold on to the Americans even before work could begin on the project and a new similar contract was signed with them on 15 April 1850.

Postal arrangements were addressed by Articles 28, 29, and 30, as follows (my translation):

Art. 28. All correspondence entering the territory of the Republic from foreign countries whatever the final destination, and to be carried on the railroad, will proceed under the control of the New Granadian Postal Authorities. These Authorities will open a current postage account on an annual basis, so that the proportion of the profits corresponding to New Granada under the terms of Article 30 of this contract can be calculated, and to ensure no fraud is perpetrated in this regard.

Art.29. As a result of the previous stipulation, the Company agrees to receive for transport on the railroad either to the next port of destination or to an intermediate address along the route, only those mail bags delivered to the New Granadian Postal Authorities; complying with all the dispositions dictated by the Executive, and also those covered by laws governing the transport of correspondence of foreign nations which has been handed over to this end by employees of the Republic.

Art. 30. The Executive will at all times determine which foreign Nations’ correspondence will be allowed to be transported by rail across the Isthmus of Panamá; but in he cases where such mailbags are carried, the contracts and pecuniary arrangements made for the carriage will fall to the Company, and all the income from these contracts and arrangements will form part of the Company’s funds, forming one of its sources of profits. To compensate for this benefit, the Company is obliged to transport on the railroad, free of charge, all of New Granada’s mailbags, and furthermore to pay to the Government of the Republic five per cent of all the monies received under these contracts or arrangements, whether coming direct from agreements with foreign Governments, other Companies, or from the general rules governing postal charges by Nations with whom the contracts were celebrated.

And it is further stipulated: 1st. However much the Company receives from these contracts, the Government of New Granada will in no case receive less than ten thousand pesos in each year. 2nd. That this payment will be in addition to the three per cent of the net profits of the business to which New Granada has a right; and 3rd., that the right of the Company to celebrate such contracts will in no way negate the contracts which now exist between the Republic of New Granada and certain foreign Nations for the transport of mail bags across the Isthmus of Panamá”.

So, whilst the Colombian Government was being paid for hosting the mails in three different ways, the British, who were already subsidising the Colombian post, began to pay twice to cross the Isthmus and the passage was eating up the whole of the postage GB/Pacific being charged. And things were to get worse. The Railroad almost went bankrupt during the construction as it confronted technical difficulties and illness. Thousands, Chinese and Irish among them, perished of typhoid, yellow fever or malaria. It struggled to reach Las Cruces, roughly the halfway point, but when it did, it cut travel time to Panamá substantially, cutting out the river trip up the Chágres. The British then moved their Consulate/post office from Chágres, at the mouth of that river, to Colón (which the Americans insisted on calling Aspinwall after an early pioneer and Director of the Railroad Company), which lay a little further down the coast, on the Caribbean, being the terminus of the railway on that side. The unfinished railway at this juncture still became the quickest route for gold-diggers to travel from the eastern United States to California to join the gold-rush. The new Isthmus crossing resulted in the European posts reaching Australia and other Pacific destinations much more expeditiously.

It will be recalled that the Convention ran for five years renewable for further five year periods, so not surprisingly on 8 October 1856 Philip Griffith, the British Chargé d’Affaires in Bogotá, wrote to Lino de Pombo the New Granadian Foreign Minister, giving notice of the non-renewal of the 1847 Postal Convention as from 17 December 1857. The letter was was published in the Gazeta Official No. 2035 dated 16 October 1856 at Bogotá. Grif th went on to express his willingness to renegotiate the treaty with speci c reference to the charges at Panamá, and this negotiation went ahead normally and produced a document dated 24 December 1859 signed by Lord Elgin & Kincardie and I. de Francisco Martín in London.

Articles 11 to 17 set out the rates to be charged into and out of New Granada and they made it abundantly clear that no postal charge would be made by New Granada on letters, book packets and newspapers crossing the Isthmus of Panamá. Articles 21 and 22 clarify the modus operandi of the transfer of mails at Colón and Panamá, and reconfirm the old system of special messengers carrying the mails (now by rail) to and fro at British expense. New Granada was granted under Article 23 a payment of a transit duty of sixpence per pound on the total amount of mail sent in transit. Article 24 stipulates that should any nation enjoy better terms for their mail crossing, then those would be immediately applicable to Great Britain. What could have been more reasonable? The Convention was ratified by the British on 13 March 1860.

Ten months later nothing further had been heard from Bogotá and Mr. Griffith was asked to “remonstrate” before the New Granadian Government. Finally Sr. de Francisco de Martín was in touch with the Foreign Office apologising for the delay in attending to this matter, from his base in Paris, blaming a very severe illness which had prevented him from journeying to the “cold and wet” of London. He goes on to state that his desire to renegotiate the terms of the new Convention (in fact, he had been accused by Mosquera of exceeding his authority in making the agreement), arguing that New Granada could not afford to lose the income from the transit charge and suggesting that each letter crossing the Isthmus should pay the basic New Granadian internal rate of postage. This was most certainly unacceptable to the Postmaster General, especially as it had come to his notice that the United States of America was not paying, so that in May 1861 a letter was written to de Francisco Martín advising that if the Convention was not ratified payments still being made to the treasury of the State of Panamá based on the original 1847 agreement would cease altogether. More than six months notice was given of this action in view of the difficulties of communicating with Bogotá – contact with the coast was interrupted because Mosquera was on the march again and preparing to take over government for the third time! Nothing was heard and on New Year’s Day 1862 the British Consul at Panamá was advised that the Postmaster General “had resolved to discontinue from this date all payments whatever for the transit of the mails”.

MOSQUERA INTERVENES

And so matters continued until the General’s arrival in London in 1865. There we saw how he encountered a means of entering into correspondence with the Foreign Ministry on questions of the Post.

The main gist of his argument for greater remuneration for the transit of the British Post across the Isthmus is set out in his letter written to Earl Russell on 14 August 1865. Here are some excerpts (my translation):

“…..Colombia suffers immeasurably from the lack of a Postal Convention and she cannot continue offering services and allowing the entrance of British mail steamers into her ports on both coasts free of tonnage duties, whilst the mailbags of all Europe are carried across Panamá. The interoceanic route causes Colombia much expense, far in excess of the income resulting from the correspondence…

Maintaining public order to guarantee European commerce en route to the Pacific nations, Australia and Polynesia requires that the Colombian Government subsidise the State of Panamá to the tune of 50.000 pesos per annum as well as the cost of an army and police presence………….. (foreign Governments) should not refuse to pay the postal charges which our Nation has established throughout the whole country and which even the Colombians pay. (On the question of the defence spending, Mosquera forgets that an army presence was required in Panamá irrespective of railways or letters. Without one Panamá would undoubtedly declare its independence from Colombia, as it had attempted to do on numerous occasions before).

Great Britain, a powerful and just Nation, has always recognised Colombia’s rights……….and we have no wish to impede the transit of the mails across the Isthmus as we could do.”

On 4 October he writes again on a different subject. He wants the United Kingdom to enter into a treaty guaranteeing the neutrality of Panamá, similar to the one which had earlier been signed with the United States of America (and a lot of good it did to the Colombians in 1903), knowing that action on the part of Great Britain would convince the French to do the same. In exchange Colombia would guarantee access to the railway and any future Panamá Canal or Canal of Darien. Neither Britain nor France took up the offer, preoccupied that such a treaty could eventually lead to an armed showdown with the USA.

The letter goes on to repeat the argument of cost – the 50.000 pesos (£10.000) subsidy, the 66.000 (£13.200) forgone in customs duties, etc. Furthermore, “no sooner had the railway been inaugurated, and through no fault of the National Government or the local State, American passengers provoked a con ict which caused great concern between Colombia and the USA, only overcome by a monetary transaction in the region of 200.000 to 400.000 dollars, which we have agreed to avoid further con ict, but which we cannot pay. I make reference to this, my dear Lord, to show how right Colombia is in wanting to clarify friendly relations in connection with the transit between the two oceans….”

The conflict refers to a riot which happened at Colón, soon after the railroad was inaugurated, and brought about by the use of the route to transport prospectors to the gold mines discovered in California. A group of goldminers and their families were awaiting onward transport to Panamá when one of their number, drunk, purchased a slice of watermelon from a local man and then refused to pay for it. When pressed further for payment the American, exercising an early right to carry a rearm, drew his pistol and promptly shot the poor man dead on the spot. This put the local populace in a frenzy and in the ensuing riot they killed or injured a number of emigrants and set fire to their property as well as the Railroad offices. Claims for compensation were made of the Colombian Government and after several years of negotiation agreement was reached (known as the Herrán/Cass Convention). The relatively few British claimants were eventually indemnified, but the Americans never were. There was simply no money. The noncompliance with Herrán/ Cass was one of the pretexts used by the USA to support the independence of Panamá in 1903 leading to the building of the Panamá Canal.

None of the General’s entreaties met a sympathetic ear and Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera left for Bogotá to assume the Presidency of the United States of Colombia once again.

DECRETO LEI DEL 17 DE AGOSTO DE 1866

Having taken possession on 20 May 1866, El Gran General delayed less than three months before issuing the following Decree Law dated 17 August 1866 and published on the Diario Ofcial (Official Gazette) No. 728 on the 28th of that month (my translation):

Executive Power of the Union

DECREE

Declaring which foreign ships are subject to the payment of tonnage dues and which are not.

T. C. de Mosquera, Gran General, President of the United States of Colombia, in use of his Constitutional powers; and

CONSIDERING

1st. – That it is recorded in the Presidential Office that the Government of Her Britannic Majesty has declared the Postal Convention between Colombia and Great Britain concluded;

2nd. – That as a result of this decision the exemptions in said Postal Convention are cancelled:

DECREE

Art. 1. The ships of those Nations with which no Postal Conventions exist will be subject to the payment of tonnage dues and will deliver up the mailbags of the respective postal administrations, or they will not be allowed to continue their voyage.

Art. 2 The ships of the French St. Nazaire line, and those of the other Nations with whom a Postal Convention exists or a special treaty guaranteeing the neutrality of the Isthmus is in force, will continue to benefit from the privileges granted under that convention or treaty.

To be communicated to whom it may concern.

Signed in Bogotá on 17 August 1866

T. C. de Mosquera

The French and the Americans were therefore exempted which left only the British. If there should have been any further doubts about intentions, in the very same Of cial Gazette and immediately below the Decree, a letter addressed to the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company (the “Mala Real Británica”) was published, advising the withdrawal forthwith of the benefits formerly afforded.

Mr. Bunch was now faced with an enormous problem. He felt responsible for the possible interruption of his Nation’s communication with the Paci c and he was dealing with a person who was irrational at the best of times and at the worst, according to his dispatches to London, unstable (to put things diplomatically!). As we have seen, exchanges of correspondence with London took at least three months and this crisis was happening now. He panicked. He wrote and told Admiral Denman of the Paci c Fleet of his troubles, and to Admiral Sir James Hope at Jamaica. Denman promised to leave a ship at Panamá from time to time to accompany developments. Sir James advised Commodore McClintock would send a ship of war to Colón, but by now Bunch’s anguished arguing was paying off with Foreign Minister Rojas Garrido and on 16 December 1966 the infamous Decree was suspended, so that Mr. Bunch had to hurriedly turn down the Commodore’s offer.

On the Coast the Decree had had mixed reactions. Frederick Stacey, the Consul at Santa Marta felt little or no effect; the locals, he said, recognised that the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company was their only lifeline to the outside world. Charles Bidwell at Panamá was paying the tonnage dues under protest but had reached a modus operandi with the local authorities and the mails were proceeding to and from Colón/Panamá. Albany de Grenier de Fonblanque at Cartagena suffers real problems. His relationship with President González Carazo is bad in the extreme. The President of Bolívar Province decides to take the 17 August Decree at its word and make life difficult for his local enemy. On more than one occasion he instructed his employees to board British ships and take charge of the mailbags and interfere with documentation. Hence the British Consul in Cartagena writes to the eet in Jamaica to “..inform…you may take such steps as you may seem expedient…..The representative of the National Government of Colombia at this port has been pleased to take possession of and open HM mails directed to me as British Consul….”. This is of course sacrilege and Captain Vesey and his HMS Doris are sent on their way. Another case of the left hand being unaware of the actions of the right!

Robert Bunch was not to know. It was not until 12 March that José María Rojas Garrido told him of the suspension of the Decree:

“The undersigned has the honour to inform the Honourable the Chargé d’Affaires of her Britannic Majesty that since the 16th December last orders have been sent to the Secretary General of the sovereign State of Panamá in order that the Bags containing correspondence should suffer no delay in the National Offices, that the operation (of receiving them) should be reduced to their delivery by the Captains of the vessels, to counting them and to delivering them immediately to the agent or employee of the Rail Road.

This operation can be performed in a single act in the presence of three officials viz, the captain of the vessel who delivers, the National agent of Finance who receives, and, at the same time, hand over to the agent of the Rail Road Company.

As his Honour will see, owing to this order which was issued by the Secretary of Finance and Internal Improvements at the date above referred to, there is no danger whatever that the Mails will be delayed in proceeding to their destination.

I inform your Honour of this as a result of the conference between us for the purpose of clearing up this point”. (Official Foreign Office translation).

THE CURTAIN FALLS

El Gran General Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera, as may be imagined, has not quite finished. He removed Mr. Dinsdale from command of the Colombia for not resisting by force the boarding by the Doris.

De Fonblanque writes to the Principle Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in London:

“I have the honour to report that the President of Colombia has been pleased to withdraw my Exequatur as Her Majesty’s Consul, in a Decree of which I beg to hand to your Honour a translation……”

In fact the Consul never left his post and was still recognised as Consul as late as 1869. On the same day he wrote a second letter:

“My Lord,

I have the honour to report that I have received a dispatch from the President of this State informing me that the President of Colombia has disapproved the arrangement made by him with Capt. Vesey of HMS “Doris”, and ordered that the provisions of the old compromise entered into with me – of which your Lordship has approved – shall be followed in future”.

Documentation from the Foreign Office is extensive and, being Victorians, naturally, legally exhaustive. The final decision, fortunately not to be put into practice, was based on “Jus Transitus”. In time of peace “there were to be no immunities to one foreign state from which others are excluded”. Britain’s rights of passage would undoubtedly have been enforced through military means.

In comparison Tomás de Mosquera left little or no documentation on his decision-making in official records in Bogotá, other than the publications in the Diario Oficial. This despite his obsession with guarding every single one of his personal letters for posterity, now available at the Mosquera Library in Popayán (except those forming part of philatelic collections around the world!). A cri de Coeur is to be found on le from the Colombian Consul in London writing home and complaining of his being left ignorant of the Cartagena proceedings and being taken by surprise by the articles in The Times. “Reports of this nature are extremely prejudicial (to Colombia), especially in the present circumstances. It was possible for me to do absolutely nothing”. I take the “circumstances” to be the poor financial straits of the Republic.

But I did find a remarkable document, hand-written and unaddressed, which I believe the Colombians call a “nota verbal” and what we might call an aide memoire. I am certain it was written by Bunch himself as it is in the same hand as the private letters sent to Hammond at the Foreign Office. We can imagine Robert Bunch handing it to Rojas Garrido as a reminder of the issues. (My translation).

“Confidential Memorandum

Her Britannic Majesty’s Government, in view of certain obstacles at some of the Colombian Ports in connection with the Royal Mail, is considering removing the Mail ships from the Ports of Cartagena and Santa Marta.

The services rendered by these ships are much more important to Colombia than to Great Britain.

It can be said that the whole of the coastal service for passengers and the post proceeds in this way, and upon this service depends communication with the United States of America.

The English (sic) Government does not pretend to deny to Colombia its right to receive and dispatch all the correspondence of the Republic in its own offices, but there is no doubt that the convenience of the public gains from the participation of the English Consuls, and at the same time mere courtesy requires their participation in the opening of the bags containing registers and other documents of the General Administration of the English Posts, the English Government does believe that it has the right to expect from friendly offices of the Colombian Government all means to guarantee the proper functioning of the service.

It cannot be denied that Colombia enjoys without cost the fruits of a first class postal service. If she does not take steps through reasonable measures to ensure the continuation of this line of communication, the English Government will have no alternative but to withdraw the service”.

The note is dated 18 May 1867. Seven days later El Gran General Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera was overthrown for the last time.

Malcolm Bentley

Sources for many documents have been quoted in the text. Other sources and further reading follow:

The British Library (Newspaper Library)

Royal Philatelic Society London (Library of Rare Books)

Post Of ce Archives 1861, 1867, POST 29/73, POST 46/35

National Archive FO 55/199, FO 85/185

Archivo Nacional, Bogotá

The West Indies and the Spanish Main, Anthony Trollope

El Gran General Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera, Antonio García, Biblioteca Luis Angel Arango, Bogotá Tratados y Convenciones, Biblioteca Luis Angel Arango, Bogotá

Vida y Opiniones de William Wills, Malcolm Deas

History of the Panamá Railroad, F. N. Otis

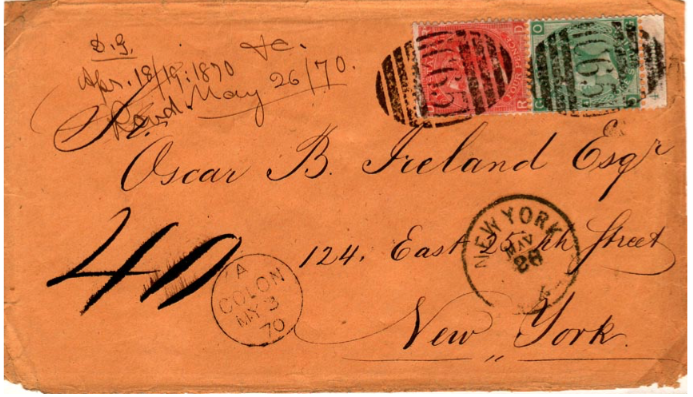

A fair number of the rarer covers depicting Great Britain/Colombia postal history of the period are addressed to an American, Oscar B. Ireland. This one which has stamps cancelled by the C65 killer for Cartagena sent in error for C56 is the only known cover to carry the C65 on distinct adhesives, 1s 4d, representing the fourth scale for the trajectory Cartagena/Colón for onward transmission to New York.